Three key findings on child poverty for Mozambican policy makers

Mozambique has experienced rapid growth and reductions in poverty over the last twenty years. The latest poverty report showed a decline in the poverty rate of about 25 percentage points over the period 1996/97-2014/15, from about 70% to 46%.

During the same the same period, many welfare indicators improved as well. Most households now have at least one member with primary education and own at least one device such as a mobile phone, TV, or radio. Access to electricity, a good quality roof and flooring are also more widespread than in the 1990s and early 2000s.

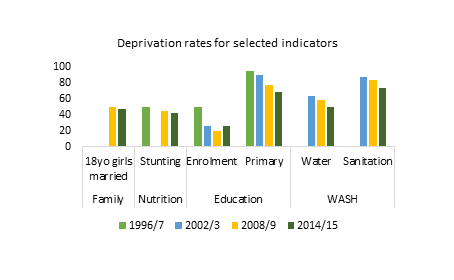

However, other indicators related to child welfare seem more resistant to change. For example, Mozambique is among those countries in the world with the highest rates of chronic malnutrition (stunting) and child marriage. These two indicators are also among those that have least improved since 1996/97.

However, other indicators related to child welfare seem more resistant to change. For example, Mozambique is among those countries in the world with the highest rates of chronic malnutrition (stunting) and child marriage. These two indicators are also among those that have least improved since 1996/97.

In a UNU-WIDER-UNICEF working paper, which Andrea Rossi of UNICEF and I presented at the recent conference on poverty and inequality, we outline three main results on multidimensional child poverty that can help inform policy to, hopefully, achieve real change.

1. One in two children in Mozambique are multidimensionally poor

About one-in-two children aged 0-17 in Mozambique can be classified as ‘multidimensionally poor’ when we consider the following deprivation dimensions:

- family

- nutrition

- child labour

- education

- health

- water, sanitation, and hygiene

- participation

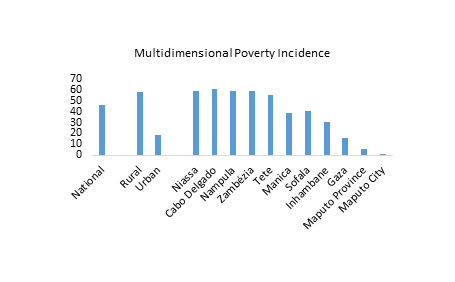

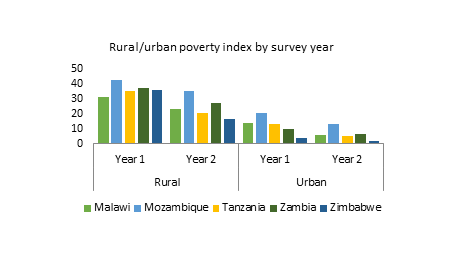

- housing

Even more striking is the divide between urban/rural areas, and among provinces (see Figure 1): the four poorest provinces — Niassa, Cabo Delgado, Nampula, and Zambezia — are about fifty times as poor as Maputo City. Moreover, multidimensional child poverty for Mozambique still exceeds that of other countries in the region (see Figure 2).

2. Child marriage and chronic malnutrition rates are high and slowly decreasing

In Mozambique, both the child marriage and chronic child malnutrition incidence rates are very high and only modestly improving over time (see Figure 3). In 2014/15, about 47% of 18-year-old young women were already married, and about 43% of children under five suffered from chronic malnutrition, which is down by only two percentage points from 2008/09. Furthermore, inequalities by province are even more dramatic for these indicators as compared to other characteristics.

Another point to be stressed is that child/adolescent marriage and child malnutrition are strongly linked: girls who get married before turning 18 start having babies very early in their life, and there is plenty of literature showing that adolescent mothers frequently give birth to malnourished children. Moreover, pregnancy in adolescence has been found to slow young mothers’ normal growth processes, worsening the risk of malnutrition for both the mother and baby.

3. Policy should strengthen interventions in the areas of WASH and education

It is not easy to provide policy recommendations in a context in which many different dimensions are so interrelated. However, taking the analysis of the determinants of stunting as a starting point, there are two main policy recommendations that the study can support.

- Invest more in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH). In all the years analysed, it is very clear that access to safe water and quality sanitation are extremely relevant and strongly needed. It is widely reported that drinking unsafe water and having access to poor sanitation conditions increase the likelihood of having diarrhea and other diseases, which in turn reduce the ability to retain nutrients leading to malnutrition. However, what emerges from the latest survey is that 42% of children aged 0-17 are deprived in their access to safe water, and 73% are deprived with respect to access to quality sanitation. In rural areas these percentages rise to 54% and 86%, respectively. At the same time, official country statistics and the UNICEF Budget Briefs for 2017 suggest that the level of government investments in these two areas did not increase over time, and reached a minimum in 2017.

- Make sure girls remain in school longer. Another important variable strongly linked to child malnutrition is the mother’s level of education, which in turn is related to child marriage. It would be important to retain teenage girls at school as long as possible, postponing marriage to a later age. Enrollment and average years of schooling significantly improved for both boys and girls over the past twenty years, but a lot has still to be done, especially to decrease dropout rates among girls and ensure education quality.

Government and other public and international institutions working in Mozambique often list child wellbeing as a priority for development, but fighting child poverty requires a serious commitment to reduce deprivation levels and the rapidly increasing spatial inequalities. This is especially true for those indicators that have improved least, and that are key to the human and economic development of the country. Interventions in these areas already exist but they clearly need to be strengthened, or, given the weak results obtained, critically redesigned.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the project partners or their donors.