Bust before boom

FINDINGS

-

Mozambique has been attracting large amounts of foreign direct investments during this decade. This should have led to a boost in economic growth but, on the contrary, Mozambique’s growth has been slowing down for several years.

- Because of the recent debt crisis, delays of gas projects and suspensions of donor grants, Mozambique faces most likely several more years with low growth, even though the country still attracts high rates of private investment.

Large flows of foreign investments have not been translated into a boom for the Mozambican economy. On the contrary, they have foreshadowed a sustained period of deep economic difficulty for the country. What is the story behind this phenomenon and what are its implications?

In 2009–11 large offshore gas fields were discovered in the Rovuma Basin, north-east of Mozambique. The country has been expected to benefit largely from new natural gas projects as several foreign enterprises have been investing heavily in the sector. Their total investments have been estimated to reach around US$100 billion, which would make the Rovuma gas fields the largest investment project in sub-Saharan Africa, if realized.

Investments running in, but growth slowing down

According to most traditional growth theories more investment means more growth. However, this has not been the case, at least thus far, in Mozambique.

National accounts data of Mozambique clearly indicate the unique nature of the period after 2010. Prior to that, the investment share of gross domestic product (GDP) in Mozambique had typically hovered at or below 20%. By contrast, in all five years 2012 through 2016 the investment share of GDP was well over 40%. This big change was associated mainly with a large surge of foreign direct investment (FDI) into the gas projects.

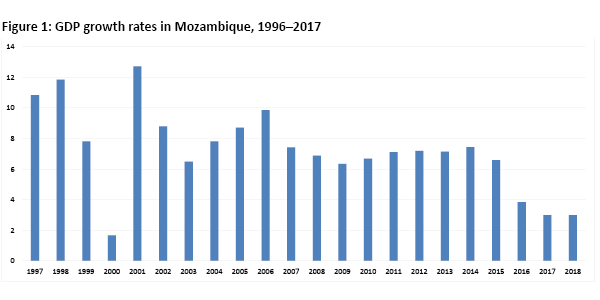

However, as Figure 1 below shows, there is no evidence of a growth spurt that might have been expected to follow from the very large FDI inflows. Indeed, growth in the period since about 2013 has been weaker than at any time in the past 20 years. Further, the projections from the IMF Regional Economic Outlook of April 2018 suggest that the growth rate through 2019 will remain below 3% and so the GDP per capita might even slightly decrease.

What is behind the growth slowdown?

The huge gas finds at the beginning of the decade led to inflated expectations of revenues from extractives. These high hopes in turn contributed to premature, undisclosed public sector borrowing, which then triggered a debt crisis in Mozambique. The gas projects have also been delayed from the earlier plans — which worsens the already difficult situation as it will take time for the revenues from the sector to flow in.

The situation could have been eased somewhat if grants from external donors had not pulled back in the face of the changing situation. However, when the undisclosed loans came out the IMF and several other donors suspended their programmes in Mozambique because of the misreporting. Thus, the country has also been hit by a reduction of grants equivalent to around 4% of its GDP, as well as by a big increase in its debt service obligations. In addition, Mozambique has suffered from lower prices for many of its key exports and the damaging effects of the droughts in 2015 caused by the El Niño. These factors combined have led Mozambique to begin the coming era of new gas production in a much more difficult situation than what was anticipated — bust has come before boom.

Building domestic capital and replacing extractives with other activities

Even when the enlarged revenues from the new gas extraction do eventually materialize, they will most likely need to be committed quite heavily to deal with the still high rates of debt and debt service. It is likely that Mozambique faces at least six more years with fiscal restraints, high debt ratios and low growth, even though the country will still be attracting high rates of private investment.

This shrinks the fiscal space of the country. Mozambique’s public sector will remain capital-constrained for several more years. Based on this result, any gas surplus, when it does begin to emerge, should arguably be concentrated on building domestic capital rather than accumulating balances in, for example, a sovereign wealth fund.

Overall, future public investment has to be much more carefully and strategically managed. Mozambique would be well advised to increase investment in transforming the economy, as extractives are, after all, a depletable resource. Because of this reality, other productive activities will in time need to replace extractives if any initial boost to growth and development is to be sustained.

IMPLICATIONS

- Mozambique’s public sector will remain capital-constrained for several more years. This implies that if/when the surplus from the gas projects begins to emerge, it should be concentrated on building domestic capital rather than accumulating balances in a sovereign wealth fund.

- Extractives are a depletable resource. This means that if any initial boost to growth and development is to be sustained, other productive activities will in time need to replace extractives to ensure some transformation of the economy.

This Research Brief is based on the WIDER Working Paper ‘Mozambique—bust before boom – reflections on investment surges and new gas’, by Alan Roe. The study has been prepared within the programme Inclusive growth in Mozambique – scaling up research and capacity.