Workforce and leadership characteristics in Mozambican manufacturing

Findings

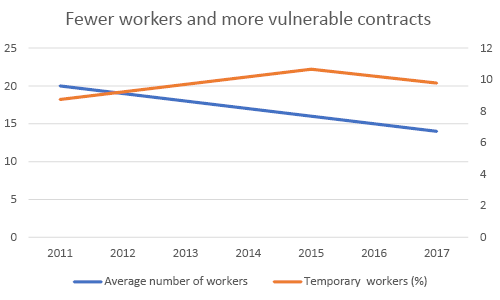

- Firms that survived the economic downturn adopted restrictive human resources management, reducing the workforce and making it more flexible, which in turn made employment more vulnerable.

- In 2017, manufacturing sector leadership appears both more satisfied and more inclined to support the training of their workers.

- Entrepreneurs reveal significant aversion to risk, which will constrain their ability to invest, both in physical and human capital.

The 2017 Survey of Mozambican Manufacturing Firms builds on data collected in 2012 from surviving firms to trace how changing economic conditions have affected the development of firms over five years. The survey also takes an in-depth look at the human factor that plays a key role in firm performance: workforce and leadership characteristics.

When the previous round of the Survey of Mozambican Manufacturing Firms was implemented in 2012, the Mozambican economy showed positive signs of stable and consistent growth. Five years later, the country is facing economic difficulties. With the ongoing credit crisis and very thin external currency reserves, Mozambique has seen its currency devalue significantly and firms saw the market narrowing. Those still operating in 2017 have depended on their leadership and their management choices regarding human resources to survive.

When the previous round of the Survey of Mozambican Manufacturing Firms was implemented in 2012, the Mozambican economy showed positive signs of stable and consistent growth. Five years later, the country is facing economic difficulties. With the ongoing credit crisis and very thin external currency reserves, Mozambique has seen its currency devalue significantly and firms saw the market narrowing. Those still operating in 2017 have depended on their leadership and their management choices regarding human resources to survive.

The 2017 survey findings provide important insights about leadership characteristics of manufacturing firms, how owners and managers regard their labour force, and their reactions to the challenging economic environment.

While more educated than average, firm leadership is highly averse to risk

Based on the 2017 survey findings, the Mozambican landscape of firm leadership, overall, has seen changes.

- The share of firms led by women increased from 5% in 2012 to 12% in 2017. This occurred through succession in firms that survived and because women-led firms were relatively more robust to the economic downturn of 2015–16. Nonetheless, the share of women-led firms remains far less than half.

- Mozambican firm managers and owners demonstrate low levels of trust in other people and very high aversion to risk, with owners of microenterprises showing extreme levels of the latter. This is manifested in their market and management decisions. Owners and managers have low propensity to offer commercial credit to business partners, reducing the scale of what is a normal avenue for companies to manage their liquidity. Conversely, they also show lack of will to contract debt, which is required for firms seeking to grow.

- Overall, Mozambican manufacturing firm owners and managers appear to have a higher than average level of education, with almost all interviewed business people having had some schooling. Around 40% had completed either the first cycle (ESG1) or second cycle of secondary education (ESG2), and about one in seven (14%) held a university degree. Interestingly, those with completed tertiary education were more likely to own a microenterprise than one of a bigger size.

- Political party membership does not seem to be a significant factor in firm performance. Other drivers, such as firm scale, formal status, and, more relevantly, the level of education of the leadership and their capacity to manage risk, significantly correlate with higher levels of labour productivity.

Firm leadership opted for downsizing and flexibility when faced with economic challenges

Survey findings also show a general level of satisfaction among firm owners with the labour force, despite movement towards more flexible contracting.

- Overall, firm owners appear quite satisfied with their labour force. More than two-thirds of the interviewees stated the quality of local labour satisfied all firm needs. Only 5% stated that it absolutely or generally did not satisfy the needs of the firm.

- The proportion of firms providing training to their workers increased from 9% in 2012 to around 21% in 2016. This is a very significant increase in investment in worker capabilities.

- Together with an overall reduction in the number of workers, manufacturing firms reacted to the economic downturn through more flexible and precarious contracts with the labour force. The proportion of temporary workers increased more than 1% between 2011–17, from 8.7% to 9.8%, and the proportion of casual workers more than doubled from 6.4% to 13% over the same period.

Mozambican manufacturing firms adapted to challenges, giving rise to new challenges for the government

Firms that survived the economic downturn were able to adjust, mostly through restrictive human resources management that reduced the workforce and made it both more flexible but also more vulnerable. Informed management choices were taken by the leadership of the manufacturing firm. These choices also highlight new challenges for the government. While flexibility is needed, the government is advised to pay close attention to the new socioeconomic risks Mozambican workers face in the new environment. Legal boundaries must be maintained, and special attention needs to be paid to the informal sector.

There are significant positive signs. The manufacturing sector’s leadership appears to be both more satisfied and more inclined to support the training of their workers in 2017 than was the case in 2012. Continuous on-the-job training and build-up of technical and organizational capacities of workers is an area where government and manufacturing firms share common objectives and where government should continue to direct investment.

However, entrepreneurs reveal significant aversion to risk which will counter their willingness to invest — both in physical and human capital. The government has a particularly relevant role here. Pursuing the government’s stated aims and parliament resolutions, the Mozambican state should assure that policies and regulations are effectively and transparently enacted by public officials, fostering a strong and predictable relationship between firms and public authorities.

Implications

- The Mozambique government should be aware of new risks faced by Mozambican workers in light of the adoption of more flexible and vulnerable forms of contracting by firm leadership. Legal boundaries must be maintained.

- The government should continue to direct its investment to vocational training and build-up of technical and organizational capacities of workers.

- The Mozambican state must assure that policies and regulations are effectively and transparently enacted by public officials, fostering a strong and predictable relationship between firms and public authorities.